Reflections on the Desert Fathers and Mothers - Part 2

Welcome to the series on the Desert Fathers and Mothers. I've written 52 articles (designed to be read over a year) on the fathers and mothers of the Egyptian desert in the 4-6th century. This week I’m reflecting on the series.

If you are just joining me on this journey through the Desert Fathers, please refer back to my initial letter explaining the goal and purpose of this series.

The Principle of the Matter...

One remarkable facet of the writings of the Desert Father and Mothers is their ability to clarify timeless principles of the spiritual life. I may not be an advocate for sitting on a pole like Symeon the Stylite (it takes a certain view of God to think that that is the method for growing in the spiritual life), but I am an advocate for the way he submitted to the fathers that cared for him (see the article on him). There are principles that guided the lives of these men and women that set them on a path of knowing Christ intimately. My goal was to give them room to breath life in to our modern culture, to make them more accessible, their teachings and stories less esoteric.

Gregory the Great and his teachings on prophecy from his “Homilies on the Prophet Ezekiel” read better than most contemporary teachings on prophecy, yet he is not widely discussed as an influential figure when it comes to the prophetic movement.

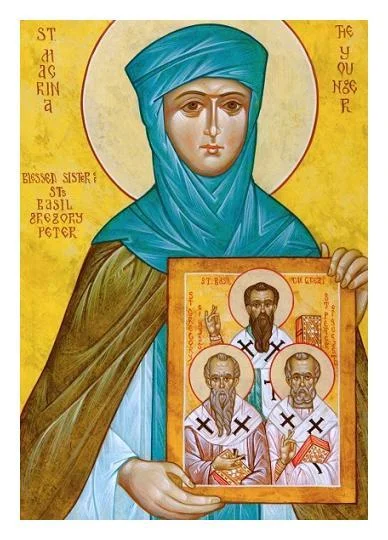

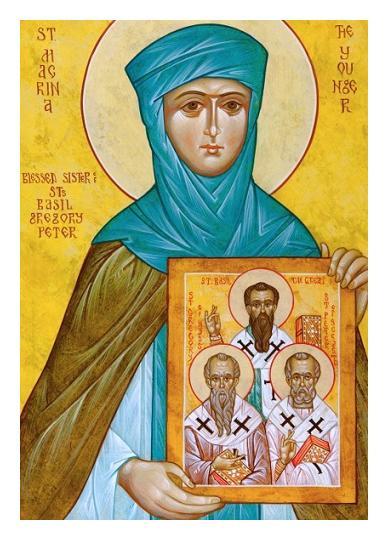

Basil the Great and his exposition on understanding the love of God as a slave, hireling or son could be a revolutionary work for most Christians when it comes to understanding and encountering the love of God. His writings stand up today just as well as Jack Frost, Jack Winter, or Brennan Manning. Macarius the Great and his teaching on the work of the Holy Spirit in the soul carries just as much weight as contemporary classics on the devotional life.

The teachings and lives of these figures have stood, at least for some of them, for 17 centuries. They have influenced church movements and great theologians throughout history. There has rarely been an age of church history that has seen such a concentrated movement that involved both men and women devoting themselves to the deep teachings and practice of life in Christ. Outside of Spain in the 16th century that saw John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila, I don’t think you can find another period quite so influential. If John of the Cross can be named the Doctor of Mystical Theology in the Catholic church, and Teresa of Avila the Doctor of Prayer, perhaps the Evangelical church can discover doctors of wisdom and the spiritual life in the Desert Fathers.

There is a quality of authorship that exists among the main Christian mystics that lends itself to an ageless influence. There are some Christian contemplative authors that were destined to influence their generation, and there are some that are destined to influence every generation. The timeless quality of the desert fathers (and the Spanish mystics John and Teresa) have kept their teachings fresh in each age. Other authors like Hildegard of Bingen and John Ruusbroec had great things to say, but there is something about their writings that saw their influence wane in all but the most devout scholars. Perhaps it is the metaphors they employ (most notably Hildegard’s elaborate angelic encounters and Ruusbroec’s astrological/topographical comparisons), or the issues they speak to, but something about their writings feel like they were destined to find their greatest influence in the age they were written.

The metaphors of fire, water, and light have a transcendent quality that brings life to the modern era reader. From Joseph of Panephysis reflecting on the will of a man becoming enflamed with God, to the hermit in the desert reflecting on the stillness of water and comparing it to the heart steeped in silence, the metaphors employed by the authors in the desert movement are rarely esoteric. They provide profound touching points that communicate deep truth today.

It is not so much the general method of prayer that has had the most impact upon me, but rather the disciplines that would help inform the disposition of the heart. Our inner life is made up of a composite of many different things: history, family of origin, present circumstances, traumatic events (both current and past), future hope, marriage, and many other factors. Absent reflection on the impact these various spheres have upon us, we remain passive responders to what moves us internally. We live externally but are moved by internal issues.

The Desert Fathers and Mothers provide an avenue for understanding the path of re-directing the internal life towards God. The internal disposition of your heart is largely based upon your present choices. Yes, there is room for internal pain and inner wounds, but the decision to deal with the pain of past trauma is largely a choice to dive deep into the heart. Internal conflict that is the result of inner woundedness is never resolved by ignorance, it is, in fact, exacerbated by ignorance.

The spiritual journey is one of healing, then one of wholeness. And wholeness is never about feeling perfect, it is about admitting and coming to grips with the vast chasm between who you think you are and who you actually are. Real wholeness lets go of the need to project ourselves as people that should be loved. This is the power of the gospel, Christ died while we were sinners. He did not die for your perfection, he died for your brokenness.